Welcome to Long Live the ABB: Conversation from the Crossroads of Southern music, history, and culture.

Last fall, I gave a presentation at the Soundscapes of the South, an international conference of music scholars held at Capricorn Studios in Macon.

It’s probably no surprise to y’all that I find tremendous meaning in place. This is as true for me camping at the farm where my pops grew up, touring Civil War battlefields, and, yes, visiting Macon, Georgia.

The conference gave me an opportunity to explore my understanding of/interest in place from literal epicenter of the Allman Brothers Band story.

This is part 1 of 2.

Why Macon?

For all intents and purposes, Duane Allman built the behemoth that became the Macon music scene. He was there because that was the home of his manager, Phil Walden.

Capricorn Studios began as a joint venture between soul music star Otis Redding and Walden. They named it Redwal.

When Redding died in a plane crash in 1967, Walden sought to get into “white rock & roll.”1 He found a new foundation in guitarist Duane Allman, who had just completed a star turn at FAME in Muscle Shoals on Wilson Pickett’s “Hey Jude”—a massive hit.

In partnership with Jerry Wexler of Atlantic Records, Walden bought out Duane’s contract from Rick Hall of FAME. The two founded Capricorn Records, an Atlantic subsidiary, as Duane’s creative outlet. It was a significant investment in a guitarist who didn’t sing or write songs.

Duane also didn’t have a band, which he rectified in March 1969 in Jacksonville, Florida—Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johanson-drums, Berry Oakley-bass, Dickey Betts-guitar, Butch Trucks-drums, and his brother Gregg on organ and vocals.

They were 5 Southern natives and one transplant, Oakley. The Chicago native moved South “as soon as I had enough sense.”2

The Allman Brothers Band moved to Macon in April 1969 and it has remained the spiritual home of the band ever since.

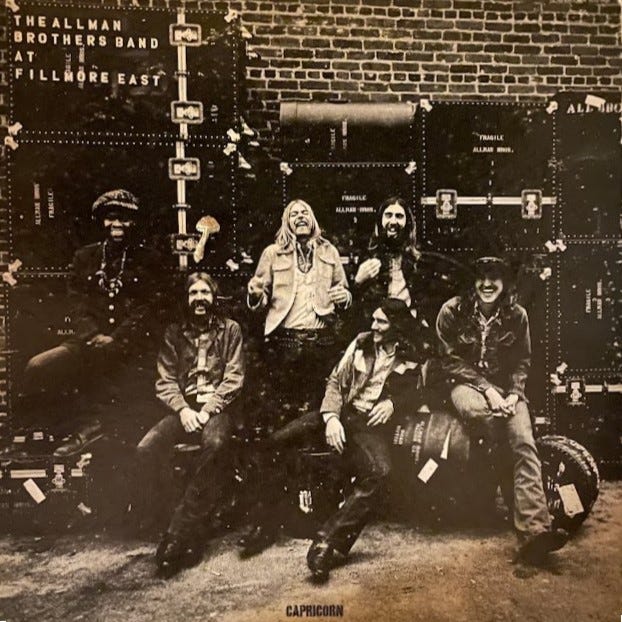

At Fillmore East was the game-changer

Capricorn Studios was the house that Duane built, At Fillmore East its cornerstone.

The album came on the heels of two (relatively) unsuccessful studio records, a self-titled debut in 1969 and Idlewild South.3

By late 1970, Duane, the band, and Walden decided to issue a live album as the band’s 3rd record. It was a gamble. Live albums were typically reserved for filler between studio records.

The ABB were relatively unknowns—no one was buying their records anyway. Walden was mortgaged to the hilt to support the band. Wexler was impatient with the return on his investment and advised breaking up the band.

The resulting album, At Fillmore East, is Duane Allman’s masterpiece as a guitarist and a bandleader.

The album is also 100% live—zero overdubs—and it catapulted the ABB to stardom, reaching gold (500,000 copies) in about six weeks. It hit #13 on the Billboard chart and firmly established the Allman Brothers Band, Capricorn Records, and Macon, Georgia, as major players on the contemporary rock scene.

The South and the Allman Brothers Band

The band was decidedly southern, musically and culturally and Walden’s early efforts to promote the band focused on a somewhat “downhome” image.4

Duane and his mates joined a long lineage of southern musicians who changed musical history by incorporating diverse sounds and influences to create distinct musical forms.

Duane is both benefactor and heir to the cultural inheritance of southern music, which, like the music of the Allman Brothers Band, kept one foot firmly rooted in the past and the other in the present.

The ABB sound typifies what historians Bill C. Malone and David Stricklin describe as core to southern musical tradition: music as “a means of release and a form of self-expression that required neither power, status, nor affluence . . . a body of songs, dances, instrumental pieces, and musical styles—joyous, somber, and tragic—that simultaneously entertained, enriched, and enshrined the musicians and the folk culture out of which they emerged.”

The Allman Brothers Band played contemporary American music that built on southern musical traditions and trends in improvisation-heavy attack favored the ultimate American musical melting pot: jazz.5

Photographer Stephen Paley was one of the earliest to document the Allman Brothers Band. He ventured to Macon in 1969 and took a series of images that captured the band as it was just beginning its journey.

Paley’s shot of the band at the Bell House at 315 College Street (now the McDuffie Center for Strings) graced the cover of the band’s debut album.

The Bell House was immediately next door to the “Hippie Crash Pad,” where the Allman Brothers Band stayed with road manager Twiggs Lyndon when they first moved to Macon.

The back cover featured a photo of the band at the Bond tomb at Rose Hill Cemetery, with Berry Oakley standing in an alcove above his bandmates.

Rose Hill Cemetery

Rose Hill, on the banks of the Ocmulgee River, provided inspiration for the band, family, and crew. Dickey Betts named “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” for a grave near the site of a favorite writing/rendezvous spot.6

Elizabeth Jones Reed Napier is buried not too far from where Duane Allman and Berry Oakley were buried after each died in a motorcycle accident within a year of each other.

Overcoming these devastating twin tragedies became the band’s hallmark.

Following Oakley’s death, the band added two new members: Chuck Leavell on piano and Lamar Williams, Jaimoe’s childhood friend, on bass.

In August 1973, the group released Brothers and Sisters7, their first alum recorded at Capricorn in Macon.

Brothers and Sisters was their biggest seller ever. It reached #1 and spawned the band’s only top-10 hit, Dickey’s “Ramblin’ Man”—which reached #2.8

In July 1973, they headlined the Summer Jam at Watkins Glen—600,000 in attendance.9

The ABB’s success was a boon to Macon, to Capricorn Records, and to Phil Walden, in particular. And it launched a movement in southern music.

Southern rock

And although Al Kooper seems to have invented the term,10 Walden essentially launched Southern rock by his embrace of Confederate imagery in marketing for his bands and his record label. He was among many white southerners who considered the flag an expression of regional pride and defiance.

How did these symbols representing an army that fought to establish a slaveholding republic in the South become innocuous?

Southern schools taught that the Confederate cause was just and that its flag signified rebellion in the spirit of the American Revolution rather than an act of treason against the United States to create a southern slave nation. The acceptance of the flag was a success of the Lost Cause narrative that framed the Civil War as a valiant defense of southern virtue against overwhelming odds11 rather than what it really was—a slaveholder’s rebellion against the United States.

Even the ABB got into the act, featuring the rebel flag and a dashing Confederate on horseback who looks a lot like Robert E. Lee in their 1974 tour promotions.

The irony of using Confederate imagery to promote a band that was 1/3 Black was lost on everyone. Neither Jaimoe nor Lamar Williams ever commented on the matter that I could find.

(More to come on this whole matter I assure you.)

The first breakup

By 1976, following a disappointing showing for Win Lose or Draw, the follow-up to Brothers & Sisters, the Allman Brothers Band broke up.

Gregg had spent more time in California with Cher than in Macon during the album’s recording. He also got enmeshed in a federal drug investigation; Dickey Betts, Butch Trucks, and Jaimoe all vowed to never play with him again.

The band was in turmoil, as was Capricorn Records, who never recovered financially from losing their signature act. They issued a poorly sequenced/edited, live album Wipe the Windows, Check the Oil, Dollar Gas, that flopped worse that Win Lose or Draw.

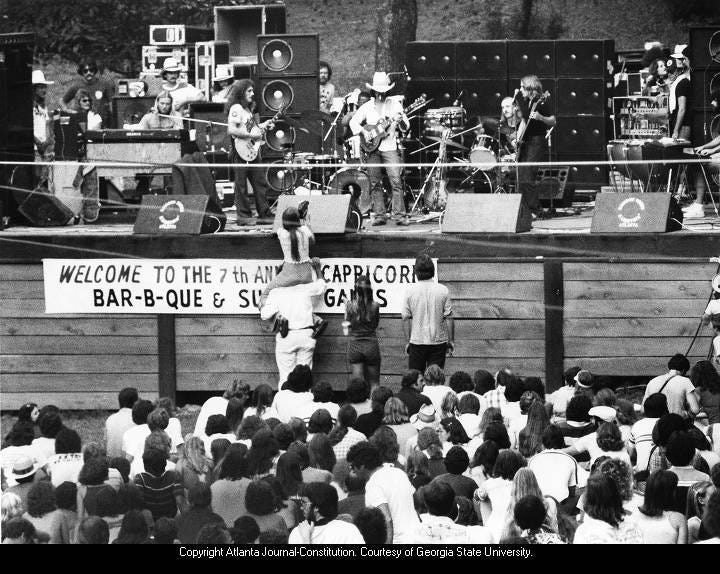

Though the ABB reunited at the 1978 Capricorn Picnic in Macon and released Enlightened Rogues on Capricorn in 1979—their ties with Macon were pretty much severed.

The ABB released 2 more albums and remained together until 1982 before breaking up for a second time.

Only Jaimoe remained in Macon, and he’d been kicked out of the band in 1981.

Things changed in 1989 with the release of the Dreams box set.

To be continued…

Neither were recorded in Macon, though they recorded demos for both records at Capricorn Studios.

Play All Night, 8.

It was in stark contrast to the pop psychedelic outfits Duane and Gregg were made to dress in as Hour Glass.

Cher’s “Half Breed” kept it from the top spot.

I’ve spoken and written about Confederate imagery and the ABB pretty extensively, including at Mercer University in Macon: “The duality of the Southern thing”

Hi! THanks for this piece. I feel like I missed "Eat A Peach", somewhere between Fillmore and Brothers and Sisters. Would welcome your thoughts.