"It was musical telepathy. We were into individual expression."

An excerpt from Play All Night

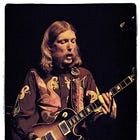

In honor of Dickey Betts’s birthday, December 12, 1943 (born in West Palm Beach, Florida), I’m sharing an excerpt from Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East.

Music was a long-standing Betts family tradition.

“I was probably five years old when I first joined in the weekly family musical gatherings, during which the combined sounds of fiddles and guitars would fill the household,” Dickey said.

The family played “country- and bluegrass-style music on acoustic instruments.” The music’s “natural beauty left a deep, lasting impression.” His love of country music and admiration for country stars Lefty Frizell and Hank Williams inspired his first goal: “I’m gonna play on the Grand Ol’ Opry.”

Dickey played ukulele, mandolin, and banjo before moving to guitar. He built his guitar chops playing Chuck Berry solos he’d memorized to Jerry Lee Lewis’s “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Goin’ On.”

“I had all these leads that I’d learned. Then I started cutting them in half and piecing them together and then, before I knew it, I was making up stuff of my own and adding to my repertoire.” A friend introduced him to John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters, and that led him to Robert Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, and the three Kings: Albert, B. B., and Freddie.

In 1960 Dickey began playing professionally, touring with the Bradenton, Florida-based Swinging Saints. The group played multiple sets a day on the midway of the World of Mirth traveling circus. “We made $125 a week, twenty to thirty shows a day from 10 a.m. through midnight,” Betts said. “Road schooling taught me that music has everything to do with what’s in your heart.”

Betts returned from the World of Mirth gig more determined than ever to play music for a living. He quit high school and went on the road, promising his mother he would eventually finish high school. He never did.

“Road schooling taught me that music has everything to do with what’s in your heart.”

Enter Berry Oakley

In southwest Florida, Betts joined forces with bassist Berry Oakley, whose commitment to original music inspired him. Dickey was fronting the Sarasota-based Soul Children. The group had some local success playing top-40 covers and scattered originals. They were making good money, $300 a week, but playing covers was a musical dead end.

Oakley showed Betts the way forward.

“Berry was pretty hip,” Dickey remembered. “He knew how to get out of clubs, which was to quit playing Top 40 shit. Berry was trying to get me into playing all originals, quit the club scene and do concerts—even if it had to be free concerts. He had all these great ideas to make us poor!”

Oakley eventually convinced Betts to pursue original music with the Blues Messengers, a group that included Oakley on bass, Dickey and Larry Reinhardt1 on guitar, Dale Betts (Dickey’s wife) on keyboards and vocals, and John Meeks on drums.

Betts saw in Oakley something many also saw in Duane: insight and wisdom that belied his youth. Oakley was convinced there was an audience for the improvisational, blues-based music they played, and he was determined to serve it.

“He was the real visionary,” Betts said.

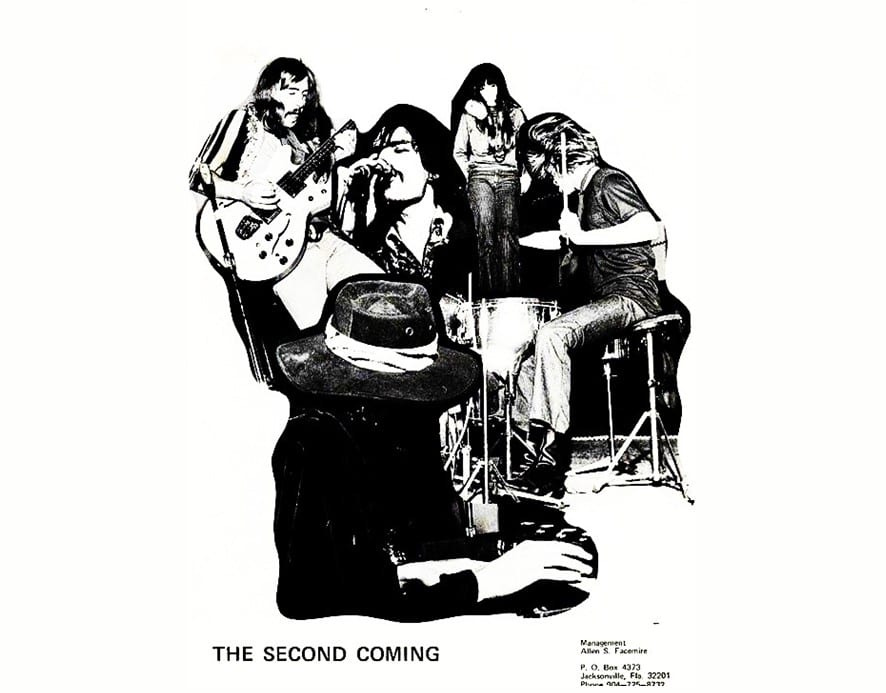

Tampa, about sixty miles north of Sarasota, became home base for the Blues Messengers, who scored a regular gig at Dino’s blues club. In 1968, the owners of The Scene, a new club in Jacksonville, recruited the band to northeast Florida to play six nights a week. Seeing the long-haired, bearded Oakley’s resemblance to popular images of Jesus, they asked the group to change its name to the Second Coming.

Dickey wasn’t the only guitarist enamored with Berry Oakley. Duane had been courting the bassist ever since they’d met in July 1968 at an Hour Glass show at the Comic Book Club. Despite Duane’s entreaties, Oakley remained committed to the Second Coming, particularly in his loyalty to and affinity for Betts

Dickey’s guitar playing had long garnered notice.

Richard Price of the Jacksonville band the Load called Betts “one of the hottest guitar players in Florida.” As Michael Ray FitzGerald remembered it, “Betts’s guitar playing was our drug,” and he recalled his disappointment when he first saw Duane with the Second Coming. “Betts stood by as most of the solos were taken by a diffident young man who looked like the Cowardly Lion and spent most of the show staring down at his Fender guitar.”

FitzGerald was outraged that “Betts let this guy hog the solos.” He was unaware he had witnessed the very beginnings of a remarkable guitar collaboration between Dickey Betts and Duane Allman.

“Betts’s guitar playing was our drug.”

Duane and Dickey

Dickey and Duane were not strangers when they crossed paths in March 1969. A fellow Floridian, Betts and Duane met in the mid-1960s before either had found his voice as a musician or bandleader.

The meeting was less than cordial.

“They didn’t take to one another just right,” Joe Dan Petty said. Recounted Betts, “I respected Duane a lot from the very first because of his guitar playing, but he was a bit standoffish.”

In spring 1969 as he courted Oakley, Duane joined the jam sessions in Jacksonville. Berry kept point out to Duane that “magic was happening when Betts was around jamming.” Simply put, Duane and Dickey sounded fantastic together.

“Duane’s melody came more from jazz and urban blues,” Betts said, “and my melodies came more from country blues with a strong element of string-music fiddle tunes. We were almost totally opposite except we both knew the importance of phrasing. We didn’t just ramble about.”

Improvisation was also key.

“When we started improvising, things fit, and we didn’t analyze it,” Betts said. “It fit together beautifully.”

Part of that magic was in Duane’s ability to improvise harmony guitar underneath Dickey. Betts recounted how “Duane started picking up on things I played and offering a harmony, and we built whole jams off of that.”

Betts loved the sound.

“When we started improvising, things fit, and we didn’t analyze it. It fit together beautifully.”

“As we started jamming,” he recalled, “we all realized that Duane and I playing harmony guitars together was something that we weren’t expecting to hear.”

Second Coming keyboardist Reese Wynans said, “Dickey’s whole thing from the first time I met him was the harmonies. He would come up with these great melodies, and he wanted to get harmonies going for them.”

Dickey’s love of harmony dated to hearing western swing on country radio. Western swing evolved in the late 1920s in Texas and the Southwest.

Its roots and influences were in country and western music, but the form included elements of pop and the folk music traditions of white and Black southerners, including jazz and blues. Its most notable performer was Texan Bob Wills, whose Texas Playboys included saxophones, trumpets, clarinets, piano, steel guitar, and drums in addition to the traditional country accompaniment of fiddle, pedal steel, guitar, banjo, and stand-up bass. Western swing also moved the guitar to a prominent position in in the music, just as Duane and Dickey would do in southern rock.

Once Dickey joined Duane’s ensemble, Oakley officially signed on as well. Duane’s band was now a quartet. Though he had some preconceived notions about the final alignment, he remained open to ideas—as long as the players were good and the music was original.

“It just formed naturally,” Betts said. “If someone fit, they stayed.”

The collaboration was exciting.

“We had discovered the very thing we had been looking for, even if we didn’t know it beforehand. We all knew that something very, very good was happening.”

EXCERPTED FROM Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East

If you liked this post, please share it with at least one person by clicking this button:

Later of Iron Butterfly and Captain Beyond.

Do you know if the ABB ever had Craig First play with them?