Remembering Berry Oakley—Brother B.O.

Help thy brother's boat across, and lo! thine own has reached the shore

Sending this out, as I do every year on November 11. If you’re a longtime subscriber, you’ve encountered it before.

On November 11, 1972, Raymond Berry Oakley III was killed in a motorcycle accident in Macon, Georgia, a little more than a year after Duane Allman’s own death in the same manner, about a quarter-mile away from Oakley’s accident site.1

Oakley is at the center of the Allman Brothers Band story, which puts him at the center of the story I tell in Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East.

While acknowledging Berry’s death was a tragedy, I choose to celebrate his immense (and unsung) impact in American music.

Below an excerpt from Chapter 7 of Play All Night and a playlist to go along with your reading

We have one big guitar and two little ones. All we need now is a bass player!

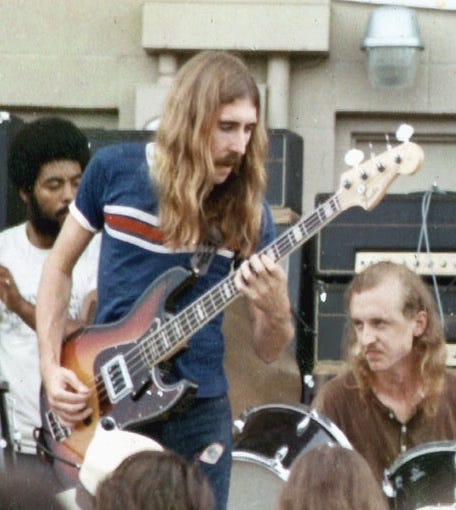

Berry Oakley was an endlessly inventive player, said Dickey Betts. “He was the real visionary…. We inspired each other’s improvisational creativity.”

Berry began as a lead guitar player in Chicago, which carried over to his bass playing, ABB roadie Joe Dan Petty observed. “Berry played a lot like a guitar player. He played a lot of notes, but he was always very precise, extremely surefooted, extremely tasteful. He had probably the best imagination I’ve heard in a bass player. He could really step out with those guitar players—and not stomp them, not walk all over what they were doing, but just ride underneath them. He was an extremely aware musician.”

“We inspired each other’s improvisational creativity.”

More lead guitar than rhythm instrument, Berry’s thundering playing took the bass in new directions. “We have one big guitar and two little ones. All we need now is a bass player!” Betts joked.

Oakley anchored the original Allman Brothers Band—a stellar lineup with players who could and would solo at any point in a song.

Their music was rooted in the blues but veered beyond the standard blues form. This inspiration initially came from Oakley, whose knowledge of and skill on blues guitar and fondness for extended improvisations glued together the various musical elements.

He could really step out with those guitar players—and not stomp them, not walk all over what they were doing, but just ride underneath them.

Psychedelic Rock2

Founded on March 26, 1969 in Jacksonville, Florida, the music the Allman Brothers first played together was a southern version of psychedelic rock, a sound that emerged from the San Francisco Bay Area in the mid-1960s.

Psychedelic rock, Grateful Dead historian Dennis McNally observes, “is music seeking transcendence through improvisation and an extremely broad understanding of what is music, including things like dissonance and feedback.”

That this same definition could apply to jazz is not coincidental. In many ways, the jazz impulse inspired the genre. The bands that played psychedelic rock, particularly those that influenced the Allman Brothers Band, played music with the jazzlike ideal of improvisation and individual and group expression.

Like jazz, it was music made in and for a particular time and place: the moment.

In their early days, the Allman Brothers Band worked tirelessly on their songs, changing arrangements, varying time signatures and tempos.

“We liked playing together so much, and someone would always come up with a new idea and keep a song alive,” Gregg wrote. “Some songs were regular length, but some were real, real long.”

Jaimoe said they’d practice the songs “four or five times to get the arrangement down, and then play them.” The band would then road-test the songs. “After we played them on a couple of gigs,” Jaimoe explained, “Duane would say, ‘On this part here, let’s do this or that instead.’”

It was music made in and for a particular time and place: the moment.

This is how “Whipping Post,” one of the band’s most famous songs, developed. Gregg originally brought the band what Dickey called a “melancholy, slow minor blues.” Oakley reworked the ballad into a driving blues tour de force, beginning with an emphatic repeating bass line that changed the song’s introduction from the more traditional 4/4 time signature to 11/8.

The change sped the song up, giving it an urgency that adapted well to the live environment. Oakley’s arrangement on “Whipping Post” is yet another example of his importance to the band.3

Lead bass

“As much as Duane,” Butch said, “Berry was responsible for what this band became.” His approach to his instrument provided texture as well as a solid foundation.

Oakley was the glue that held the rhythm section together. But the bass is also a melodic instrument, and this is where Oakley excelled in the musical structure of the Allman Brothers Band.

“Oakley was a very instinctive bass player,” Gregg said. “He knew when to just sink into the repetition of a song, so the bottom was there for the rest of the band.”

Said Jaimoe, “Berry was the first cat who allowed me to relax and enjoy his playing,” he said.

Perhaps most importantly, Berry’s playing fit Duane’s vision, Gregg said. Oakley was “the bass player my brother had always been looking for. They were so tight—spiritually, musically, brotherly. They really had a thing going.”

Oakley’s lead bass became a major element of the band’s developing sound.

Berry’s off-the-cuff melodies sparked the band’s improvisation. “There were times when Berry would be playing a line or phrase and Duane would catch it, then jump on it and start playing harmony,” Betts recalled. “Then maybe I’d lock into the melodic line that Duane was playing, and we would all three be off. Berry would take over and give us the melody.”

“Berry was the first cat who allowed me to relax and enjoy his playing.”

While Duane didn’t model the Allman Brothers Band on the Grateful Dead, the San Francisco band was the Allman Brothers’ closest corollary, and from their earliest days, people compared the bands.

Formed near San Francisco in 1965, the Grateful Dead were among the first and most notable American rock bands. Unlike the ABB, their oeuvre was rooted in folk, not blues, but both bands excelled at R&B and blues covers. Each group had its share of instrumental virtuosos, though even hardcore Deadheads acknowledge the Dead’s lineup lacked the across-the-board virtuosity of the ABB.

“The bass player my brother had always been looking for. They were so tight—spiritually, musically, brotherly. They really had a thing going.”

The Dead were among the bands that ushered in the rock era in America.

The Allman Brothers Band followed in their wake.

Rock was an evolution of popular music that transformed rock ’n’ roll from dance music to music experienced live. Rock shows were an individual and collective cultural experience that blurred the lines between musician and audience. “[Rock] spoke exclusively to youth,” wrote historians Bill Malone and David Stricklin. “[It] reflected a non-conformist, anti-establishment youth culture…whose traits became virtually worldwide: long hair, unconventional dress, illicit drug use, sexual freedom, and hostility toward or disinterest in politics or civic and religious authority figures.”

The transition from rock ’n’ roll to rock changed live music into a full-fledged musical event. Concerts became participatory art. “The live setup,” critic Richard Meltzer notes, “adds visual accompaniment to mere music and a space for it to fill and bounce around at least metaphorically.” Concerts provided the backdrop for cultural expression in tandem with audiences.

This mindset was especially true for the Grateful Dead, whose music and live shows quenched what Jerry Garcia called the “desire for meaningful ritual.”

Psychedelic drugs played a huge role in the events as the musicians grew less inhibited onstage. “Playing high instilled in us a love for the completely unexpected.” Listeners were active participants. “Each person deals with the experience individually,” Garcia saod. “But when people come together, this singular experience is ritualized.”

Listen to “Dark Star,” the Grateful Dead’s psychedelic masterpiece from their 1968 album Live/Dead, to hear the Dead’s influence on the ABB. The twenty-three-minute track is primarily instrumental; the band is in constant communication throughout multiple movements, tempos, and sounds.

On “Dark Star,” Lesh plays lead bass throughout, never losing the rhythm while having an intense musical conversation with his bandmates, holding the music together while playing along with and encouraging Garcia’s lingering leads. The jam revolves around Lesh, as every Allman Brothers Band jam would revolve around Oakley.

EXCERPT FROM Play All Night! Duane Allman and the Journey to Fillmore East

Psychedelic Lead Bass

That’s how I like to think of Berry Oakley.

I’ve long believed his tragic death (on a motorcycle and just 13 months and a few blocks from the site of Duane’s own) obscures his immense talent and influence that extends well beyond the Allman Brothers Band. But it damn sure starts there.

Berry has a zillion great moments in his relatively brief 3.5 year ABB career. At Fillmore East is full of them as is Eat a Peach. His basslines on “Wasted Words” and “Ramblin’ Man”—the last two songs he recorded—reflect his versatility within the ABB’s sound.

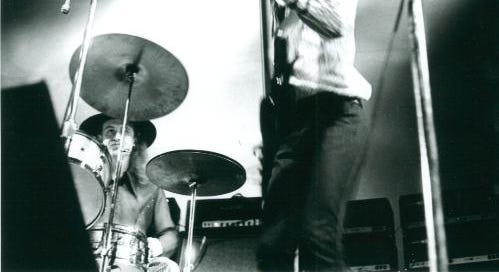

I’ll leave you with this from early in the band’s career, “Mountain Jam” from the February 1970 Fillmore East run opening for the Dead. Berry’s bass just thunders throughout

And, of course, “Little Martha” from the Dreams box set, with Berry’s bass mixed back in.

“Brother B.O.” and the posts’s subtitle (a Hindu proverb) are inscribed on Berry’s tombstone.

Phil Walden first promoted the ABB as an “Experimental Blues Rock Music Feast.” Read more here:

It also should have earned him a songwriting credit, and I’ve never fully understood why he doesn’t have a co-write.