The impossibly good Allman Brothers Band of Macon, Georgia

Bud Scoppa's April 1971 feature on the ABB

Welcome to a new year of conversation from the crossroads! Glad to have you here.

Some quick housekeeping before I share a great primary source from Bud Scoppa.

1. Paid subscribers

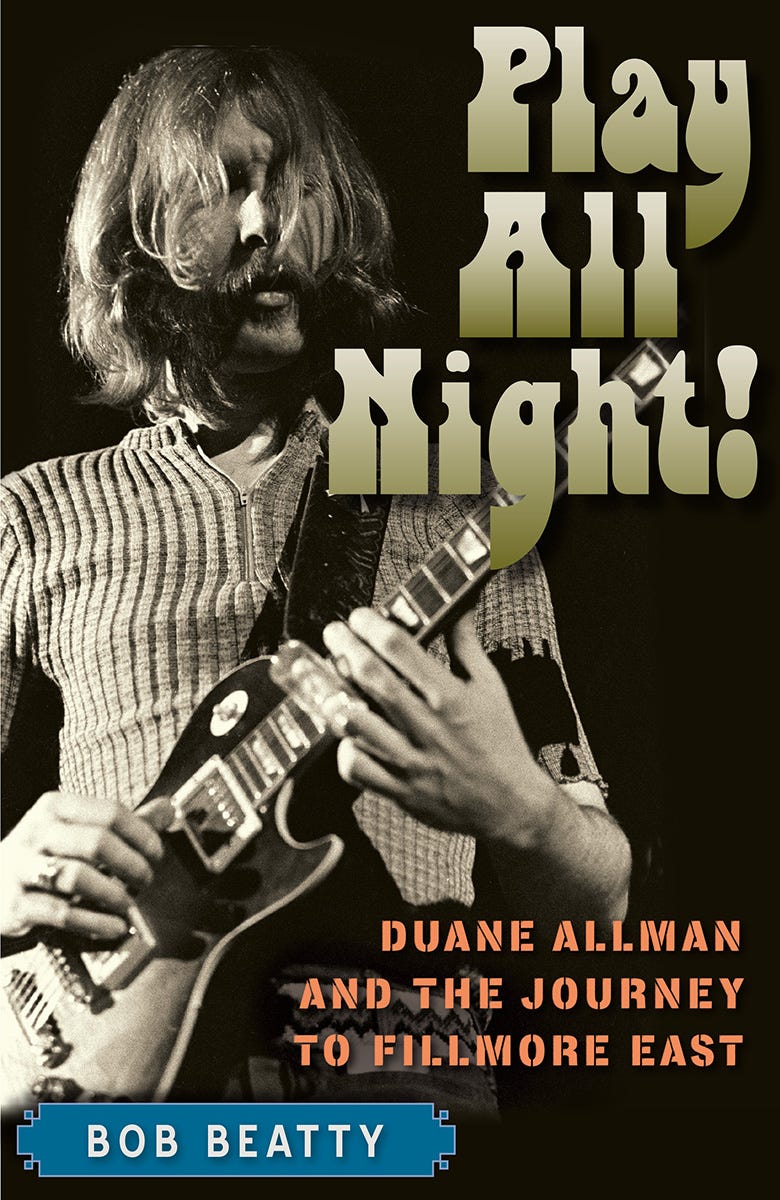

Make sure you’ve gotten your exclusive Play All Night book cover downloads. I’m really proud of these pieces I commissioned from one of my favorite digital artists, Brett Underhill/Porkchop Bob Studios. Here’s a preview. Details here.

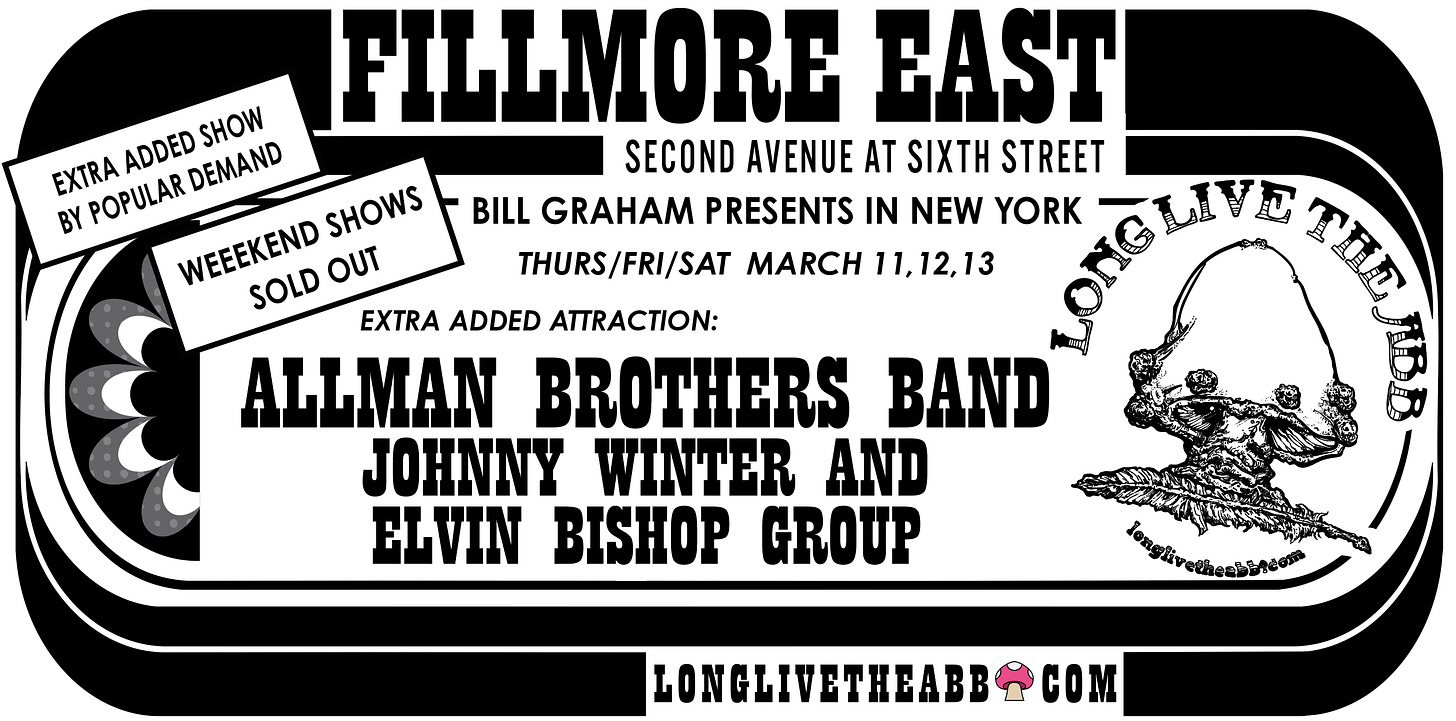

2. Long Live the ABB artwork

More than an ornament, this glorious piece from the hand of Macon-based Psychodelik Pete is something I’m keeping out year-round. I have one final piece left from of a set of 10. Cost is $70 postage paid. Let me know by filling out the form here.

Calendar

I put together a kick-ass calendar for 2025. Something tells me you might dig it. I know it’s only relevant for another next week or so, so I wanted to get it in front of you. Preview below.

To purchase: https://calendar.longlivetheabb.com/

Did Santa bring you Play All Night?

If so, drop me an email and I’ll send you out some swag.

On to the festivities…

Freeing another primary source from DEEP in the archives.

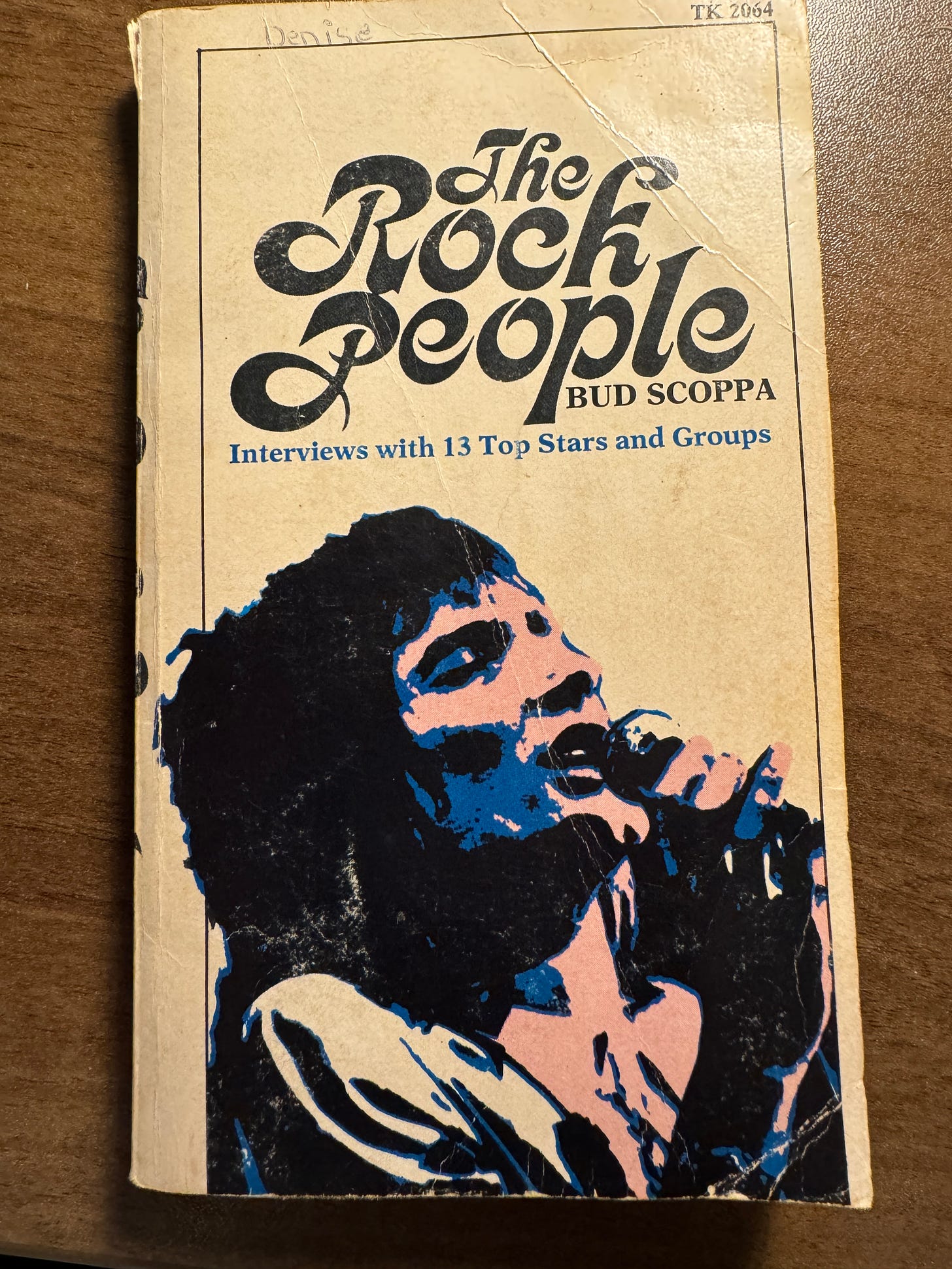

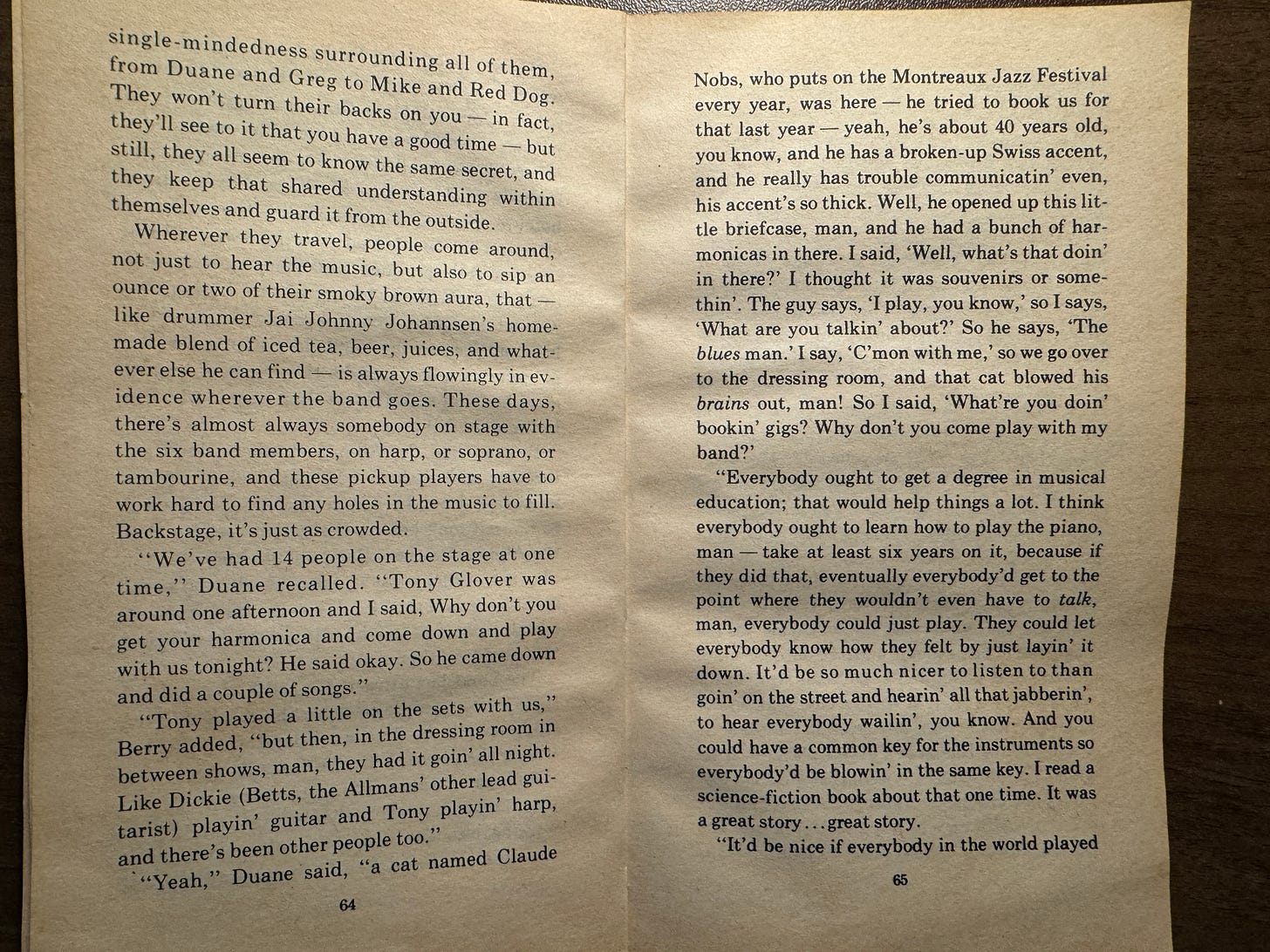

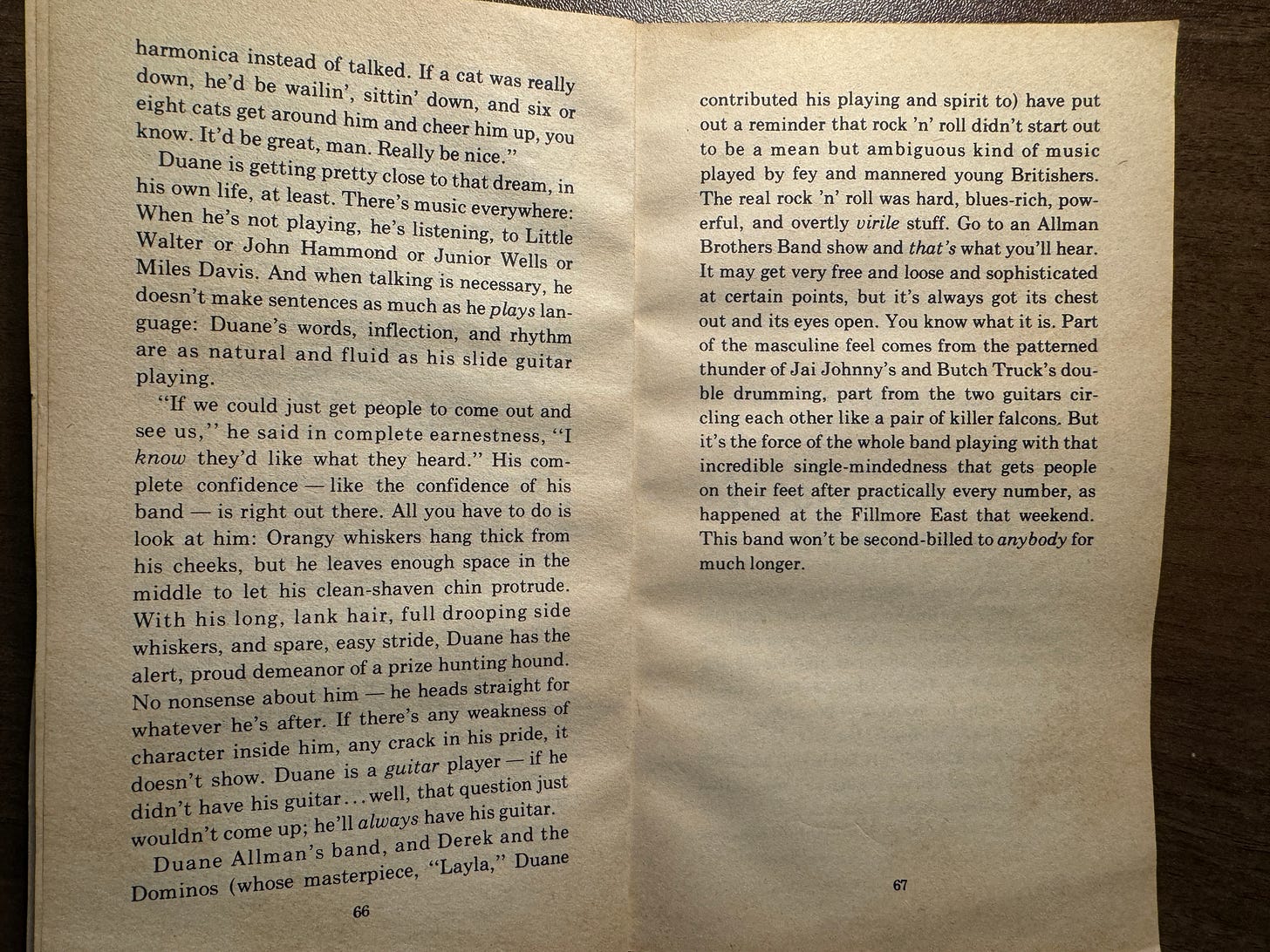

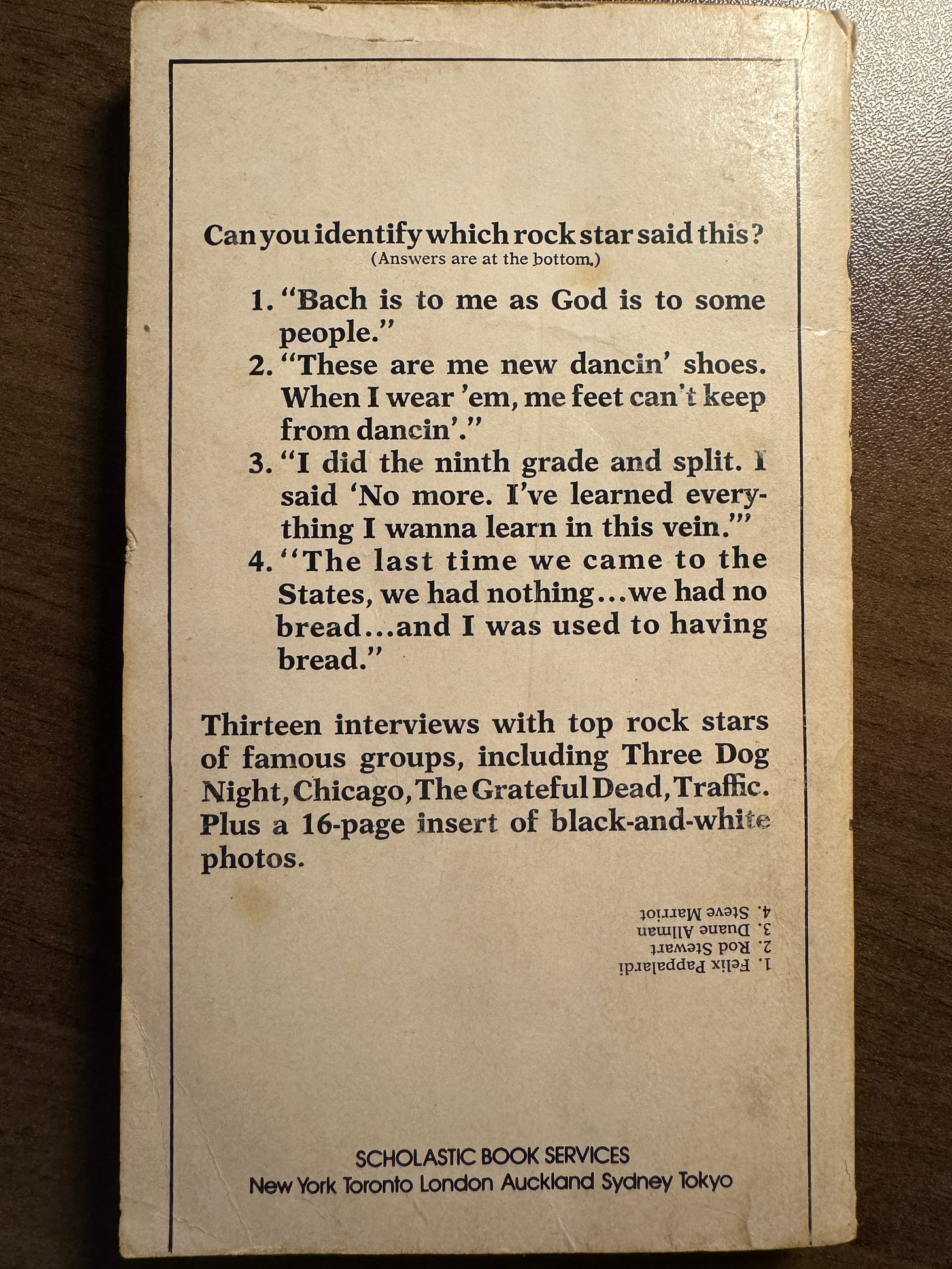

I first came across this piece in a 1973 Scholastic Books1 publication called The Rock People: Interviews with 13 Top Stars and Groups. It’s a collection of Scoppa’s interviews with (you guessed it) rock musicians that originally appeared in Crawdaddy, Rock, and Circus.2

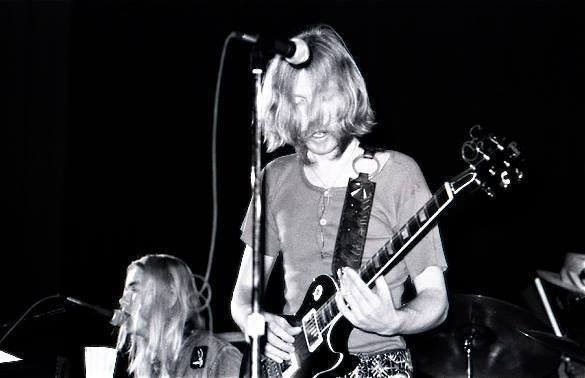

Chapter 4 is titled “The Allman Brothers Band” but is really all about Duane Allman. Scoppa talked with Duane & the band in New York City in March 1971 as they recorded At Fillmore East.3

Here’s the text verbatim. I’ll do a marginalia edition of this interview at a later date.

The Allman Brothers Band

Duane Allman, universally acclaimed guitarist and cofounder of the Allman Brothers Band, was killed in a motorcycle accident in October 1971. This article was written six months before his death.

Right now, the impossibly good Allman Brothers Band, of Macon, Georgia, is just entering its prime as a performing unit. I saw the group in 1970 and decided it was just about the tightest instrumental group I'd ever heard. Unbelievably, when I saw them again a year later, they were even better.

I'm convinced this is one of the great bands of the 70s.

Who else could combine Muddy Waters and Miles Davis and make it all come out sounding like powerhouse rock ‘n’ roll? They get standing ovations after practically every number they play these days, and that's exactly what happened the night I saw them.

After their two sets that evening4, several group members stayed up the rest of the night with Elvin Bishop (who was sharing the Fillmore bill with the Allman Brothers and Johnny Winter). Seems that Bishop has accumulated hundreds of vintage rock ‘n’ roll singles—not the kind Sha Na Na parodies, but the dark, sinful rock ‘n’ roll Southern boys were raised on—and programed them onto cassettes. He even cataloged them—neatly printed the name of each tune in this book as thick as the Macon Telephone Directory (including Yellow Pages).

“I spent my junior high school and high school years down in Daytona Beach, Florida, and it was not very conducive to musical development at all. But there was still some good rhythm and blues music on the black stations and that was great—you could get WLAC down there. So that’s where I got most of my background.

Everything I heard, just about, was on one of those stations—unless, you know—I was a record freak. I never did have enough money to get into a lot of records, but I bought as many as I could afford.

The first record I ever bought was ‘Young Love,’ by Sonny James. Borrowed a buck from my mother to get that one. Boy. what a waste of money.... I was 10 years old at the time.”

From listening to all that good music (not counting “Young Love”), it was a simple step to wanting to learn how to play it.

“I had a kid livin’ next door to me, man—this ol’ country guy. I was livin’ in a housing project with my grandmother in Nashville—used to spend the summers up there. Just to get away from Florida for awhile, you know, I’d go visit my grandma.

And this kid named John Banion lived across the street and he had an old Silverstone guitar.5 John taught me a couple of chords on it and stuff, and I got kinda interested in it, and my brother Gregg did too. In fact, Gregg learned to play first, and I kinda lost interest in it, man.

Then, when Gregg was 13 or 14, he decided he wanted a guitar. And one year, for Christmas, I got a little Harley Davidson motorcycle, you know. I tore the bike up in about two months, and the guitar still looked brand new. I had nothin’ to do again, so I said to Gregg, ‘Why don’t you teach me a lick or two on that?’ So he taught me to play. Later on he got interested in organ—keyboard and stuff—and I just kept playin’ guitar.

I took a few piano lessons, when I was real young. My teacher, man, she was always telling me ‘What beautiful hands you have’ and all this stuff.

Man, I was scared of her; I don’t know why. She kept tellin’ me, ‘You oughta study,’ and everything, and the last thing I said to her, I said, ‘The reason I don’t wanna do this is because I’m never gonna need it for the rest of my life. I’ll never need this damn music—take it and keep it.’

I left, and she died before I could get back and apologize to her. I always regretted that really bad—she was a good woman. Really good to me, and patient. When I’d get a weird-on or have a tantrum, she’d just sit there, you know, and let it run out and then try to get me to play somethin’.

I also took a little trumpet in school one time—in the marching band. Couldn’t make it.”

The marching band wasn’t the only part of school that Duane couldn’t handle.

“I never finished school, man. I’d ask ‘em, ‘Well, why am learnin’’ this? you know. ‘Well, never mind why—you’re gonna need it.’ And, you know, man, I wanted a little more proof than that. I did the ninth grade and split. I said, No more. I’ve learned everything I wanna learn in this vein.’ I didn’t go along with that at all.”

Down in Florida in those days, a guy didn’t need a diploma if he knew how to play. Although Duane was just a kid, before long his band was making $75 a night—so much money that they had to play only a couple of nights a week to get by. There were lots of young musicians making a living then. But unlike most, Duane and his brother Gregg kept getting better they weren’t satisfied with being club hacks playing copy-music. The mediocre players kept dropping out, and the bands gradually got sharper and leaner. Duane and Gregg were still in the middle of it.

Meanwhile, way up in Chicago, a kid named Berry Oakley was wishing he was someplace else.

“I was born there and lived there ‘til I was about 17. I started playing—let’s see I was a freshman in high school—I started playing when I was about 15, I think, or 14.

Me and a couple other cats, we said to each other, ‘Hey, let’s start a rock ‘n’ roll band.’ So we says, ‘Okay, well, let’s take lessons or something.’ And we did that ‘til we could figure out three chords and then we started a band, you know, about six months later.

But then when I was 17, man, I was just lookin’ for something to do. I wanted to get away, you know, and this band6—from down South—they were tourin’ up there, and I liked ‘em. One of the cats got drafted, so I wanted to sit in with them. I said, ‘You need another guitar player? I’d like to do it,’ you know.

And they said okay, and they were leavin’ to go the next couple of days, so I just split. I been down South ever since, and I really dig it, you know, a lot more than I did up there.”7

Duane, Gregg, and Berry leapfrogged their ways through a succession of cities and bands—Allman Joys and Hour Glasses in various incarnations—and bounced inevitably toward each other.

Through all those five-sets-a-night, six-nights-a-week, empty Marlboro boxes, dingy hotel rooms, and sleepless nights, the process of elimination continued, slicing away all but those most determined, and those most devoted to that thick, dark, lumpy music. Living that way either makes you sickly and depressed or lean and pragmatic—and older than other people your own age (maybe the result of logging more hours of wakefulness than people who live in standard fashion).

By the time the Allman Brothers Band got together and settled in Macon, each of the six musicians knew he was good, having proved it to himself long before.

It stands to reason that the Allman Brothers Band should know how to play better than most—ask anybody who’s ever seen them, and they’ll tell you it’s true.

Even on a bad night, there’s hardly anybody playing that could cut them.

The band has attracted a cadre of people to support it—people to drive the truck, lug the equipment, mix the sound, cook the chicken, answer the phone, book the dates. Nobody calls it an organization—it’s just a bunch of people who tend to hang together—but it’s a hard-working, efficient bunch of people, nevertheless, just like the band itself. There’s an aura of single-mindedness surrounding all of them, from Duane and Gregg to Mike [Callahan] and Red Dog.

They won’t turn their backs on you—in fact, they’ll see to it that you have a good time—but still, they all seem to know the same secret, and they keep that shared understanding within themselves and guard it from the outside.

Wherever they travel, people come around, not just to hear the music, but also to sip an ounce or two of their smoky brown aura, that—like drummer Jai Johanny Johanson’s homemade blend of iced tea, beer, juices, and whatever else he can find—is always flowingly in evidence wherever the band goes.

These days, there’s almost always somebody on stage with the six band members, on harp8, or soprano9, or tambourine10, and these pickup players have to work hard to find any holes in the music to fill.

Backstage, it’s just as crowded.

“We’ve had 14 people on the stage at one time,” Duane recalled.

“Tony Glover was around one afternoon and I said, Why don’t you get your harmonica and come down and play with us tonight? He said okay. So he came down and did a couple of songs.”

“Tony played a little on the sets with us,” Berry added, “but then, in the dressing room in between shows, man, they had it goin’ all night. Like Dickey (Betts, the Allmans’ other lead guitarist) playin’ guitar and Tony playin’ harp, and there’s been other people too.”

“Yeah,” Duane said, “a cat named Claude Nobs, who puts on the Montreaux Jazz Festival every year, was here—he tried to book us for that last year—yeah, he’s about 40 years old, you know, and he has a broken-up Swiss accent, and he really has trouble communicatin’ even, his accent’s so thick.

Well, he opened up this little briefcase, man, and he had a bunch of harmonicas in there. I said, ‘Well, what’s that doin’ in there?’ I thought it was souvenirs or somethin’. The guy says, ‘I play,’ you know, so I says, ‘What are you talkin’ about?’ So he says, ‘The blues man.’

I say, ‘C’mon with me, so we go over to the dressing room, and that cat blowed his brains out, man! So I said, ‘What’re you doin’ bookin’ gigs? Why don’t you come play with my band?’

Everybody ought to get a degree in musical education; that would help things a lot. I think everybody ought to learn how to play the piano, man—take at least six years on it, because if they did that, eventually everybody’d get to the point where they wouldn’t even have to talk, man, everybody could just play.

They could let everybody know how they felt by just layin’ it down. It’d be so much nicer to listen to than goin’ on the street and hearin’ all that jabberin’, to hear everybody wailin’, you know. And you could have a common key for the instruments so everybody’d be blowin’ in the same key. I read a science-fiction book about that one time. It was a great story…great story.

It’d be nice if everybody in the world played harmonica instead of talked. If a cat was really down, he’d be wailin’, sittin’ down, and six or eight cats get around him and cheer him up, you know. It’d be great, man. Really be nice.”

Duane is getting pretty close to that dream, in his own life, at least.

There’s music everywhere. When he’s not playing, he’s listening, to Little Walter or John Hammond or Junior Wells or Miles Davis.

And when talking is necessary, he doesn’t make sentences as much as he plays language.

Duane’s words, inflection, and rhythm are as natural and fluid as his slide guitar playing.

“If we could just get people to come out and see us,” he said in complete earnestness, “I know they’d like what they heard.”

His complete confidence like the confidence of his band—is right out there. All you have to do is look at him: orange-y whiskers hang thick from his cheeks, but he leaves enough space in the middle to let his clean-shaven chin protrude.

With his long, lank hair, full drooping side whiskers, and spare, easy stride, Duane has the alert, proud demeanor of a prize hunting hound. No nonsense about him—he heads straight for whatever he’s after.

If there’s any weakness of character inside him, any crack in his pride, it doesn’t show. Duane is a guitar player—if he didn’t have his guitar...well, that question just wouldn’t come up; he’ll always have his guitar.

Duane Allman’s band and Derek and the Dominos (whose masterpiece, Layla, Duane contributed his playing and spirit to) have put out a reminder that rock ‘n’ roll didn’t start out to be a mean but ambiguous kind of music played by fey and mannered young Britishers.

The real rock ‘n’ roll was hard, blues-rich, powerful, and overtly virile stuff. Go to an Allman Brothers Band show and that’s what you’ll hear.

It may get very free and loose and sophisticated at certain points, but it’s always got its chest out and its eyes open. You know what it is. Part of the masculine feel comes from the patterned thunder of Jai Johanny’s and Butch Truck’s double drumming, part from the two guitars circling each other like a pair of killer falcons.

But it’s the force of the whole band playing with that incredible single-mindedness that gets people on their feet after practically every number, as happened at the Fillmore East that weekend.11

This band won’t be second-billed to anybody for much longer.

HERE’S IMAGES OF THE TEXT

You can download the PDF here.

All hail Scholastic Books!

🍑You know what to do, give the Amazon algorithim overlords a tickle to let other cool people know about Play All Night.

I’m assuming Scoppa is talking about Friday, March 11, the first two nights of the recording for At Fillmore East.

Gregg tells a different, much more detailed story in his own book.

That’s the Roemans, Tommy Roe’s backing band. There’s video of Berry with the Roemans here. He’s on the right, on bass. When he joined the Roemans, bass was was completely new to him.

This is some of the most extensive coverage Berry got in this era. Most of the attention was on Duane.

Thom “Ace” Doucette.

Bobby Caldwell played percussion during the Fillmore East sessions on March 11, though not tambourine that I know of.

This Substack is going to go down as the ultimate, definitive encyclopedia on the Allman Brothers Band. Thank you!