Turning Points: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Change

Adapted from Chapter 15 of An AASLH Guide to Making Public History

Adapted from Chapter 15 of An AASLH Guide to Making Public History

I started Chapter 15 of An AASLH Guide to Making Public History with some background on the theme for the 2013 AASLH Annual Meeting: Turning Points: Ordinary People, Extraordiary Change.

We used the 50th anniversary of the Birmingham Summer (dubbed “Project C” by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference) as a launching point for a conference held in Birmingham.

For me, no one exemplified the theme more than the soldiers of the Civil Rights Movement. This includes Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth of Birmingham’s Bethel Baptist Church, founder of the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, and co-founder of the SCLC. (Here are my thoughts on Rev. Shuttlesworth.)

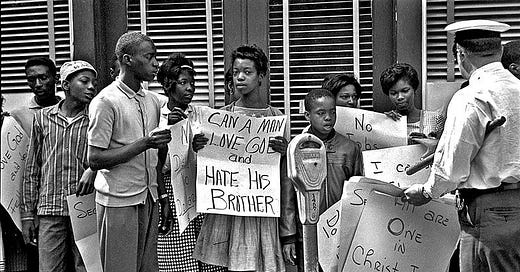

It also includes several thousand youth between the ages of seven and eighteen who marched in Birmingham in summer 1963. This led to brutality at the direction of Birmingham’s Commissioner of Public Safety Bull Conner: police beatings, firehoses, police dogs, and the like. The national public outcry was significant and helped turn the tide for the Civil Rights Movement itself.

It was truly a Turning Point, one created by Ordinary People who made Extraordinary Change.

The history discipline writ large has turned toward the activities of everyday people in the construction of the narratives of the past. Katherine Kane and Liz Silkes of the International Coalition of Sites of Conscience wrote the following about Ordinary People, Extraordinary Change. It widened the perspective from the lessons of the Civil Rights Movement; it challenged history professionals to closely examine their own work with Birmingham’s lessons in mind.

In “What Kind of Ordinary Will You Be?,” chapter 16 of An AASLH Guide to Making Public History, Max A. van Balgooy articulates three turning points for history organizations: (1) doing history with a passion, (2) making history meaningful, (3) pursuing an aspirational vision. These three elements, he argues, can turn the ordinary into the extraordinary for our institutions.

Passion: For me, passion comes first. I strongly believe that if you lack passion for history and for our work, you’re in the wrong field. There are many days when passion is what carries us through.

Leadership is one of the ways history is essential. History provides inspiration and role models for meeting the challenges that face us. In history we find countless individuals (Reverend Shuttlesworth, for example) who passionately believed their endeavors and offer us examples to follow in our personal and professional lives. It’s more than okay to carry with us love for a particular person and/or event from history. Our visitors will relate to this and it may inspire them as much as it has inspired your own pursuit of history.

Meaning: How do we best use the lessons of history to build activities that directly confront issues, those that make history interesting and relevant and useful, and human? How do we connect history to people’s lives? (It’s our job to, by the way, not theirs.)

“Ours is a unique value proposition,” maintains Steve Elliott, soon to retire as CEO of the Minnesota Historical Society. “We have…all kinds of stuff. But it’s what we do with our stuff that matters. Our wedding dresses, forts, and moccasins in and of themselves aren’t valuable unless we make them meaningful…. Our stories of struggle, success, and failure; triumph and tragedy; and progress are not merely interesting, or just instructional, well-selected, and compellingly interpreted. They can be transforming.” That, my friends, is the very defition of making meaning!

Aspirational: Pursuing an aspirational museum makes the work of history much more important than simply preservation of the past. For those who are aspirational about our work (and I am one), history can and does play a role in connecting individuals to each other. As former AASLH Council chair David Crosson noted, “We have to accept the vision of historical salvation, that [history organizations] do not exist for the sole purpose of imparting historical information... but we actually have a meaningful role to play in changing people’s lives.” Our institutions, he continued, “should, and could, move visitors to lamentation, contemplation, repentance, and perhaps even action.”

Public historian Denny O’Toole, former coordinator of the long-standing Seminar for Historical Administration, once noted, “Doing public history well delights and enriches private lives. It provides context and perspective for understanding events of the moment and helps inform and add ballast to the ideas and opinions we all bring to our lives as citizens of this republic.”

“The prerequisite for a just society,” Darren Walker of the Ford Foundation wrote recently, “has always been the engagement of its people.” Kane, Silkes, Elliott, Crosson, O’Toole, and many others (myself included) call for us to aspire to use history for wider engagement with the present and future. Thus, we answer not only Walker’s call but also that of our communities, our field, our discipline, and our nation.

What are your thoughts on Turning Points: Ordinary People, Extraordinary Change? How do you employ Max van Balgooy’s articulation of the need for Passion, Meaning, and Aspiration in your life and work (and life’s work)?

A twenty-year veteran of the nonprofit world, Bob Beatty is founder of The Lyndhurst Group, a history, museum, and nonprofit consulting firm providing community-focused engagement strategies for institutional planning, organizational assessments, and interpretive direction.